The role of search in your site can be a hot topic. Sometimes there is pressure to make it a giant bandage to cover poor navigational structure, and other times it’s included just because “every site needs search.” Let’s look at three pervasive myths about search and two questions that will help us create a strategy unique to every site.

Misconceptions About Search

Myth #1: Site Visitors Prefer to Find Information With Search

Researchers have worked to combat this myth and have found that site visitors’ behavior does not naturally trend toward search first, even when searchers know exactly what they’re looking for. User Interface Engineering’s Jared Spool says “Users often gravitated to the search engine when the links on the page failed to satisfy them in some way. Users seemed to use the search engine as a fallback after failing to pick up scent (a sense of the correct path to take to locate information) on the home page.” As it turns out, search plays just one part in the search for information, and it’s usually not the first.

In one study (324kb, PDF), only thirty nine percent of participants looking for specific content searched for keywords first. The rest did what the researchers called “orienteering”, or reaching target content through a series of small steps that brought them increasingly closer to it (like typing in URLs and clicking links).

Myth #2: Every Web Site Needs Search

Search can be a very expensive and time consuming feature to get right; it’s better to have no search at all than a poor search.

For example, let’s say your site search doesn’t support synonyms. If a search for “record player” turns up no results even though your site has articles filed under “turntable,” visitors may assume you don’t have what they’re looking for and leave.

Consider also research done by User Interface Engineering (UIE). They studied people trying to find certain content on the United Postal Service web site (ups.com). When participants used search to find their target content, twenty percent continued looking after they had found it. When participants used browsing and not search to find their target content, sixty-two percent kept looking around the site after they found their content. During their session, the latter group ended up seeing almost ten times more site content than the first group!

Myth #3: Advanced Customizable Search Will Solve Our Problems

Although it’s useful to a minority of people, advanced search is too complicated to figure out for general web users. It’s not a matter of intelligence, but rather an obstacle for our innate desire to have the perception of quick progress.

This was explained in the “paradox of the active user,” a term dating back to IBM’s User Interface Institute in the 1980s. It says that, although people may value extra features in theory, they really want to start using a piece of software right away without obstacles (e.g. reading a manual or adjusting settings).

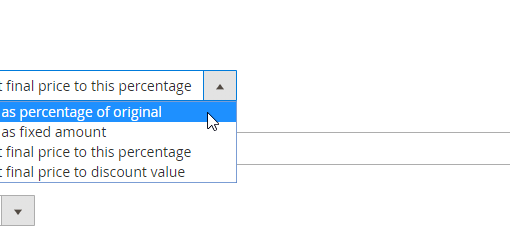

Search is no different. Even if adjusting some settings in a customized search experience will yield better results or save time in the long run, people are much more likely to start searching without noticing or putting effort into adjusting them. Simple filters after a query to hone results are more effective than a complex search interface which makes the task seem overwhelming. If you need a reminder of where the average person stands in internet knowledge, this short Google video about browsers is a good eye-opener.

Two Questions to Help Define the Role of Search

Misconceptions aside, search is still a very important framework for the web. How do we decide how search should be used on our own web sites? Here are some helpful questions to ask that will help you or your team find a direction:

What is Your Content How Will People Find It?

The first content consideration is quantity and format. Do you have one site or many sub-sites? Is your site small, medium, or large? How does the navigational structure currently support accessing that content? Smaller sites with descriptive and helpful navigations may not need to implement search at all, while very large sites wouldn’t be able to support discovery without a fully featured search system.

Discovery happens with two types of information foraging: known-item and exploratory. When people are looking for “known items,” they have unique specifics about that item that can be searched directly (e.g. a book title). Exploratory search happens when users don’t know precisely what they are looking for or how to get there (e.g. finding the best travel supplies for an upcoming trip or looking up medical symptoms).

Most of your site content is probably a fit for exploratory searching, as the majority of sites are. This means that visitors will be most successful when orienteering for content, using search as a supplement to other tactics.

Who is Using Your Site and How Are They Accessing It?

Knowing the age, location, tech-savviness, and devices of your target audience will help hone your search strategy. For example:

- Searchers who are visiting your site on mobile find the experience easier and more enjoyable if text prediction is employed, even if it doesn’t actually save them time.

- Elderly people tend to want more feelings of efficacy around their internet experience and also experience generally more anxiety about technology than their younger counterparts.

- Younger people who are educated about how search engines work may create longer, more targeted, search strings. This will lead to very precise results, which may be so precise that they leave out some content which could be useful. In this case, the SERP (search engine results page) has the responsibility to guide these users to other relevant content.

If you have personas written, this is the perfect time to pull them out. Create or review scenarios that each persona would go through to find information on your site, thinking critically about how their specific situations may influence your search implementation.

Constructing a Strategy

The organizational wrestling match that can exist between navigational structure and the role of search can be avoided with a proper understanding of what search can and cannot do. Search is not a magic box nor just an ornament; it is part of the dynamic conversation with people who are trying to learn, purchase, sell, relate, and be entertained online.

When our product teams function as a cohesive unit, the focus shifts from features to people. Designers work with developers to solve problems by creating a customer-centric product that promotes the business, all of which give the marketers something fantastic to talk about!

Related posts:

- Creating Typography for a Client Site: Case Study

- User Interviews and Tests with Site Visitors

- Busting the Mobile Web Content Myth

- Creating a Marketing Strategy for Your UX Skills

- Use Data-backed Personas to Shape UX Design Decisions

If you want to read more from Emily, subscribe to our fortnightly web design newsletter, the SitePoint Design View

Emily Smith

Emily Smith is an information architect and usability consultant for the web and Apple devices. She co-works with other web professionals in Greenville, SC and can be found online at emilysmith.cc.

![UNIX treats all devices as files [closed]](https://www.rubin.com.np/wp-content/themes/customizr/assets/front/img/thumb-standard-empty.png)